MIND MAP

FLOW CHART

LAYOUT DESIGN

ICON Design

Typography

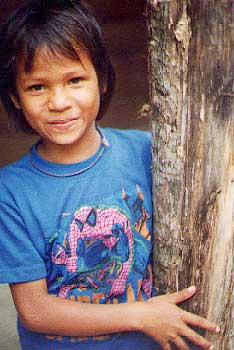

Orang asli Orang asli Orang asli Orang asli

interview with Mr. Antares

… is what a large number of Orang Asli tribes call our planet.

The Orang Asli constitute Peninsular Malaysia’s indigenous folk

and there are at least 18 distinct tribes.

The word tanah means “earth” or “land” and tujuh means “seven.”

So Tanah Tujuh literally translates as “Seventh Land”

or “Seventh World” or “Planet Seven.”

What does 7 represent in numerology and symbology?

There are 7 major keys in the octave,

7 primary colors in the chromatic spectrum,

7 main chakras in the bioenergetic system,

7 days of the week,

7 hills, 7 sisters, 7 dwarfs,

7 wonders…

Antares is a writer, musician, and visionary

who moved out of the city in 1992 and found himself living amongst the Temuan

(second largest of the peninsular Orang Asli tribes) in the heart of the Malaysian rainforest,

a few miles from Gunung Raja - a mysterious, mist-enshrouded mountain

revered as the birthplace of a postdiluvian humanity.

ISBN 10: 978-983 3221-13-4

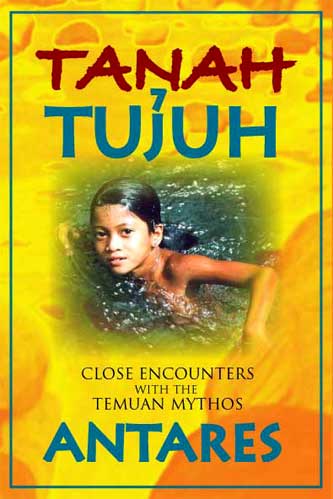

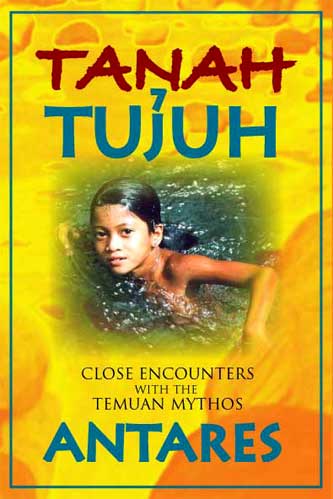

Tanah Tujuh: Close Encounters with the Temuan Mythos

chronicles Antares's initiation into a fast vanishing aboriginal cosmomythology

that offers an alternative view of reality.

Copiously illustrated with sketches and photographs,

a Temuan Glossary, and a foreword by eminent anthropologist,

Robert Knox Dentan.

SAMPLE CHAPTERS

Song of the Dragon

Seeing Beyond 3D

Blinded By Greed

Spiral Stairway to the Sky

Temuan Glossary

Published in April 2007 by

ORDER ONLINE!

The Orang Asli constitute Peninsular Malaysia’s indigenous folk

and there are at least 18 distinct tribes.

The word tanah means “earth” or “land” and tujuh means “seven.”

So Tanah Tujuh literally translates as “Seventh Land”

or “Seventh World” or “Planet Seven.”

What does 7 represent in numerology and symbology?

There are 7 major keys in the octave,

7 primary colors in the chromatic spectrum,

7 main chakras in the bioenergetic system,

7 days of the week,

7 hills, 7 sisters, 7 dwarfs,

7 wonders…

Antares is a writer, musician, and visionary

who moved out of the city in 1992 and found himself living amongst the Temuan

(second largest of the peninsular Orang Asli tribes) in the heart of the Malaysian rainforest,

a few miles from Gunung Raja - a mysterious, mist-enshrouded mountain

revered as the birthplace of a postdiluvian humanity.

ISBN 10: 978-983 3221-13-4

Tanah Tujuh: Close Encounters with the Temuan Mythos

chronicles Antares's initiation into a fast vanishing aboriginal cosmomythology

that offers an alternative view of reality.

Copiously illustrated with sketches and photographs,

a Temuan Glossary, and a foreword by eminent anthropologist,

Robert Knox Dentan.

SAMPLE CHAPTERS

Song of the Dragon

Seeing Beyond 3D

Blinded By Greed

Spiral Stairway to the Sky

Temuan Glossary

Published in April 2007 by

ORDER ONLINE!

please tell me about your book and Tanah Tujuh what do you think about it?

Behind my rented bungalow was a dilapidated bamboo hut. I got an Orang Asli family to fix the roof and floor and we became friends. This marked the start of my contact with the tribe. When the property changed hands in 1994 I decided to build my own hut just beyond the Orang Asli village. My daily contact with the villagers made me interested in learning Temuan and noting down whatever folklore remained. I actually carried a notebook around, pretending I was Carlos Castaneda.

Within a few years my informants began to die of old age and ill health – and I realized the tribal memory would die with them, leaving the younger generations with only the TV to tell them stories. So I began to flesh out my notes, beginning with a Temuan glossary and whatever myth fragments I had gathered from the elders. As problems with loggers and the Orang Asli Affairs Department emerged, I started writing articles for magazines and newspapers.

Bureaucrats assume the Orang Asli have no religion because they have never opened their hearts and minds to their rich mythology. Indeed, the myths inform their spiritual life – and by ignoring the Orang Asli’s stories, the State is effectively negating their spiritual connection with the land and thereby turning them into cultural and political nonentities. Anthropologists call this ethnocide. As a writer who happened to be living amongst the Orang Asli, the task fell upon me to document as best I could the Temuan’s folklore before it completely evaporated.

What we can learn from orang asli and their way of life?

Mythology cannot be quantified or approached through left-brained logic. As soon as you make a conscious effort to enter into the fluid, dreamtime reality of folktales, your cellular wisdom begins to activate and your imagination gets fired with the essential mysteriousness of existence. It becomes obvious that viewing the world through economic filters is woefully inadequate and can only lead to ontological myopia.

Indeed the myriad problems faced by modern man issue from his disconnection from heart wisdom and disengagement from his own soul. The remedy cannot be found in the realm of intellect – only in the realm of intuition. And intuition comes from listening attentively to the still inner voice that speaks to the pure of heart. The Temuan people – despite the cultural attenuation wrought by close proximity to rapid, relentless “development” – still retain a childlike innocence when compared with their urbanized cousins. Their belief system allows for the free operation of magic and can restore our jaded sensibilities, freeing us from the mechanistic thought patterns of an industrialized, dehumanized worldview. In other words, these long-forgotten folktales have medicinal value – indeed, they might well constitute the long sought-after cure for cancer (a disease of alienation from and disattunement with the web of life)!

How long did it take you to write the book?

About two years, working in dribs and drabs. I didn’t have any deadline. Sometimes that is a real problem!

please tell me about your writing process.

Most of the story fragments began as three or four scribbled sentences in my notebook. Details were vague and few stories connected. However, having been interested in mythology for years, I had a fairly broad overview of creation myths and folkloric themes from around the world. Since I wasn’t addressing an academic audience I took the liberty of adding my own interpretations to many of the myth fragments. The process was akin to imagining the whole beast from several loose bones.

There were several essays documenting the less-than-pretty political realities of being an Orang Asli that eventually found a home in the appendix section of the book.

So, to answer your question, the process was initially very haphazard. However, over the years I reshuffled the material until some sort of flow became apparent.

Was it difficult getting publish your book?

After several chapters had been written in 1997, a selection was published in magazines. By 1998 the bulk of the book was done. Collecting Temuan words for the glossary continued. Then news of the Selangor Dam project broke and the book was put aside while I dedicated all my energies to halting the destruction. My attention was focused on bullding the Magick River website (www.magickriver.net), which became a sort of escape from the horror and pain of seeing my beloved landscape torn up by excavators and bulldozers. I worked on a 52-minute documentary (Guardians of the Forest) about the impact of the dam on the Temuan and it was hoped that there would be money left over from the production for Magick River to publish Tanah Tujuh. As to be expected the documentary overran its budget.

The next project was a CD of Mak Minah’s healing songs (Akar Umbi – Songs of the Dragon) and, once again, there was hardly any local media support. The CD moved too slowly to accrue any real profits that could be used to print the book. So I began asking around. A friend who offered to help find a publisher took a copy of the manuscript and then sat on it for over a year. I lost interest in the book for a while and almost forgot I had a more or less complete manuscript in my file cabinet. In early 2006 I met Robert Knox Dentan, an eminent anthropologist who had spent years with the Semai tribe. I passed him a copy of the manuscript and a few days later received a hand written preface from him. He said it deserved to be published and that gave me the impetus to email Raman Krishnan of Silverfish Books. Imagine my delight when Raman responded a couple of weeks later saying the book was excellent and that he would publish it.

What advice have you for budding writers?

I haven’t had enough books published to be in a position to offer advice. But I guess it’s essential that you trust your own voice. Don’t get too self-conscious about style, focus on substance!

No comments:

Post a Comment